Bachelor thesis applying an early MARISCO approach for a situation analysis of the Alto Purus National Park, Peru Teresa L. Reubel, Robert S. R. Williams, Danilo Jordan, Juvenal Silva & Eddy Torres

à see below

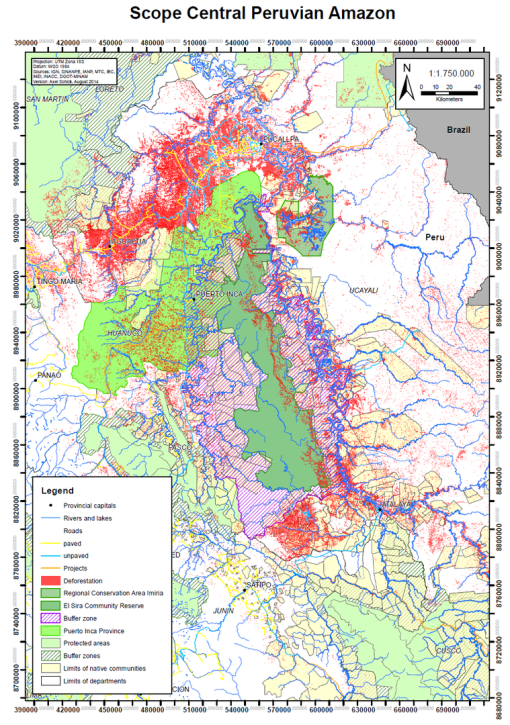

Central Peruvian Amazon: communal, provincial and regional biodiversity management within and outside protected areas

Axel Schick, Christoph Nowicki & Pierre L. Ibisch

General setting

The key goal of the “Biodiversity and Climate Change Project in the El Sira Community Reserve” of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH was to reduce the vulnerability of the El Sira Community Reserve and its buffer area to problems relating to human-induced climate change and other negative impacts arising from human activities. The main aims of the project were to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions through the conservation of forests as carbon sinks, and to facilitate the adaptation of ecosystems and communities to the effects of climate change. Two staff from Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development were contracted to analyse the vulnerability of the area together with practitioners employed by local organisations participating in the project.

Following on from the work in the El Sira Community Reserve a second project, “Biodiversity conservation through co-management in the Peruvian Amazon” (CoGAP), was organised to build on the achievements of the El Sira project and to share experiences and findings with other communal reserves . The CoGAP project aimed to promote the protection of biodiversity through co-management and the sustainable use of natural resources in selected conservation areas and their buffer zones. The main findings of the El Sira project was the need to up-date continuously and adapt the initial formulated situation analysis to changes and developments over time in order to achieve efficient co-management. Furthermore, the legal requirements needed to be revised, partners strengthened and participation mechanisms improved.

Box 1: Central Peruvian Amazon

The region analysed during the three assessments is characterized by a relatively flat landscape with alluvial plains dissected by an isolated, undulating mountain range. High mountains in the west are a watershed to numerous rivers and streams feeding in to the upper Amazon basin. The seasonally flooded river basins along the Ucayali belong to the Iquitos Várzea Ecoregion (Várzea means "flooded forests"). Most of the area is covered by wet lowland rainforests of the Ucayali and Southwest Amazon moist forest ecoregions. Premontane moist forests and cloud forests of the Peruvian Yungas are found at higher elevations. The variations in soil conditions and topography at both the local and regional level make the forests biologically very rich. Rainfall ranges from 1600-2500mm annually, and elevations range from 200-2500m above sea level.

The El Sira Community Reserve is located in the central Peruvian Amazon and covers the area between the Ucayali River on the eastern side and the Pachitea River to the west. It is situated in the departments of Pasco, Huánuco and Ucayali and the provinces of Oxapampa, Puerto Inca, Coronel Portillo and Atalaya. It is the largest community reserve in Peru with an area of 616,413 ha and a buffer area of 1,032,340 ha [Inrena, 2001].

The Community Reserve El Sira was established in 22nd June 2001 by the Peruvian State in order to conserve biological diversity for the benefit of the indigenous ethnic groups living in the area [Decreto Supremo N° 037-2001-AG. 22 June 2001]. Community reserves represent a special category within the Peruvian Protected Area System. In contrast to other protected areas, the management of community reserves is shared between the state, in this case the National Service for State Protected Nature Areas (SERNANP), and an administration partner, a so-called Ejecutor de Contrato de Administración (ECA) [Castro, Alfaro & Werbrouck, 2001]. In El Sira this partner is ECOSIRA, a local organisation representing 69 of the indigenous communities in the area around the reserve and a rural community. ECOSIRA is jointly responsible for managing the area and has a contract for an unlimited term to manage the reserve according to the special regime established for community reserves.

El Sira is known for its spectacular scenery and distinctive geological formations. The protected area covers the Cordillera El Sira, an isolated mountain range that gradually rises from the left bank of the Ucayali River, around 75 km south of the city of Pucallpa. It is one of the eastern most of the Andean ranges and has a peak 2,230 meters above sea level. With its rugged terrain and an extension over five altitudinal belts (from 200 to 2,230 m above sea level), the community reserve displays a wide variety of habitats including tropical lowland rainforest, tropical humid jungle, very humid tropical highland transitional jungle to tropical humid jungle, very humid tropical transitional jungle to tropical highland rainforest, tropical highland rainforest and very humid tropical highland jungle. Tropical pastures, locally known as pajonales [Scott, 1979], and dwarf forests with naturally bare rocky areas on the peaks are found in the southern part of the massif. Due to its geographical isolation El Sira is home to a diverse and unique flora and fauna. At least 300 bird species, 124 mammals, 140 reptiles and 109 types of fish have been identified so far, although the real numbers are believed to be higher [Mee et al., 2002; Gonzalez, 1998]. The Community Reserve is botanically rich and harbours many endemic species, including the El Sira curassow (Pauxi unicornis koepckeae), tanager (Tangara phillipsi) and hummingbird (Phaethornis koepckeae) and at least three tree species and four amphibian species unique to these mountains [Weske & Terborgh, 1971; Graves & Weske, 1987; Aichinger, 1991; Duellman & Toft, 1979; Lotters & Hensl, 2000; Monteagudo & Huaman, 2010].

The local population of the buffer area is similarly diverse, including native communities of ethnic groups belonging to the Ashaninka, Asheninka, Shipibo-Conibo and Yanesha, as well as rural communities of migrants from the Andes [Benavides, 2005].

As mentioned above, part of the El Sira Communal Reserve and its buffer zone belong to Puerto Inca, the easternmost province of the department of Huánuco. Puerto Inca has an extension of 9,913.94 km² and roughly covers the Pachitea River watershed, which has its origin in the mountains in the west. Around 32,000 inhabitants live within the administrative district, which was founded in 19th November 1984. The province is the epicentre of the structural changes that currently are transforming the Central Peruvian Amazon. The remoteness of the region and lack of enforcement institutions or personnel has attracted various illegal practices in the past including coca cultivation, gold mining, poaching and illegal logging, much of which persists today. . The construction of roads in recent years has sparked interest within the private sector to capitalise on the rich supply of the province’s natural resources Timber and agricultural corporations have started to replace the local cattle farmers that arrived from the Andes during the settlement movement of the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years, mining and oil concessions were leased in great numbers covering now almost the entire area [Finer et al., 2008; Finer & Orta-Martinez, 2010].

It is very likely that the pressure will increase in the near future once the road project designed to connect the city of Pucallpa with the Brazilian road network is completed. [MTI 2012]. The new road will have major consequences for the Regional Conservation Area Imiría, which is located in the east of the El Sira Community Reserve. Following the Ucayali River upstream, the conservation site covers an area of 135,737.52 ha on the left river bank, including two black water lakes that represent unique ecosystems within the region. The protected area is located within the watersheds of the rivers Tamaya and Inamapuya and belongs to the district of Masisea in the Coronel Portillo province, which belongs to the department Ucayali.

The Regional Conservation Area Imiría was founded in 15th June 2010 and is managed and financed by the Regional Government of Ucayali. It is the first protected area of its kind in the region and receives technical support from SERNANP. It allows the direct use of natural resources according to management plans, approved, supervised and controlled by the corresponding authority. The construction of roads and other infrastructures is also permitted, in accordance to local law.

The main features of the protected area are the two black water lakes Imiría and Chauya. Lake Imiría has an area of 34.74 km² and is connected with the Tamaya River. Lake Chauya is not connected with any river and is only accessible by crossing Lake Imiría. It covers an area of 44.33 km². Both water bodies belong to the Tamaya Watershed and are located in notable depressions created by geological processes. Additionally, the protected area covers a series of smaller lakes, namely the lakes Panuco, Shapaja, Chica, Lagarto and Garza [Gobierno Regional de Ucayali, 2004], as well as some oxbow lakes along the Tamaya River [Envirolab Peru SAC, 2010].

Six Shipibo-Conibo communities and nine settlements of migrants from the Andean area are located within the protected area. The economy of the local population depends mainly on the fish they catch in the lakes, but timber and non-timber forest products, such as bijao leaves (Calathea lutea), are also sold.

Among the fauna, pink and grey river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis; Sotalia fluviatilis), manatees (Trichechus inunguis), yellow-spotted and arraus river turtles (Podocnemis expansa, Podocnemis unifilis) and Paiche (Arapaima gigas) are of special interest in terms of local conservation. For instance, the Amazon manatee is a vulnerable species with decreasing population trend (Marmontel 2008).

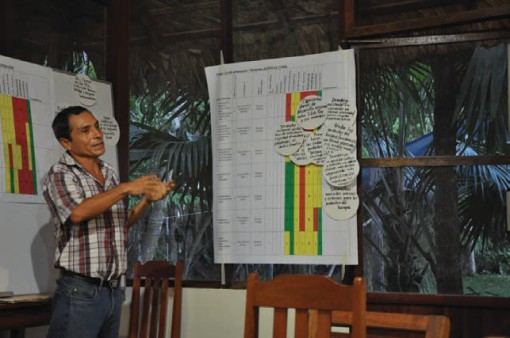

Workshops and work flow

The assessment of the region started in 2011, when the vulnerability of the El Sira Community Reserve and the surrounding area were analysed during three workshops held between April and September in the cities of Pucallpa and Atalaya (Ibisch & Nowicki 2011/2012). Around 45 participants, including representatives from indigenous communities, ECOSIRA, local governments, the regional government of Ucayali, SERNANP, local universities, NGOs and the GIZ conducted a systemic vulnerability analysis. The president of ECOSIRA and the SERNANP official responsible for the area took an active part in the workshops.

During a flight over the protected area the consultants were able to identify at first hand the extent of the protected area and also some of the more obvious potential threats. Later on, these impressions were shared with the participants during the workshops.

In April 2011, a vulnerability assessment, the first stage in the MARISCO method, was carried out at two separate workshops held in Atalaya and Pucallpa. The working groups developed a complex situation analysis as a critical part of the vulnerability assessment.

The participants worked through an iterative process, contributing their knowledge of the status of the reserve and its forests. The work involved the discussion of technical presentations, as well as analysis in plenary sessions and working groups. The systemic analysis was displayed on coloured cards representing different classes and attributes.

The outcomes of the two analyses were combined and presented in an interim report.

The third workshop designed to cover the next set of steps in the MARISCO cycle was carried out in September with participants of both the Atalaya and Pucallpa workshops. First, the participants validated the results of the combined situation analysis, and then evaluated the existing management plan in the context of those findings, with the intended objective to formulate effective and realistic strategies to target existing and future threats to biodiversity.

During the workshops, the participants engaged in a collective learning process to improve their knowledge of climate change, vulnerability concepts and risk, taking into account the current situation of the reserve and potential future scenarios, including anticipated climate and socioeconomic changes.

Significant strategic gaps were identified following a detailed analysis of the relationships between current conservation strategies and recognised threats and risks, and the extent of vulnerability caused by the deficit between threats and current action. The fact that some of the strategies themselves might have been vulnerable and did not always prove effective was also discussed. These observations served as input for the development of new complementary strategies, which were evaluated in a semi- quantitative manner.

The assessment of the region continued in 2013 when the Imiría Regional Conservation Area and the Puerto Inca Province were analysed. Since the workshops followed the same approach as the assessment of the El Sira Communal Reserve, the process will not be described in as much detail.

While the management plan for the conservation site was being prepared, a vulnerability assessment of the Imiría Regional Conservation Area was conducted in order to ensure the plan was risk-robust and practice-orientated.

In August 2013, an Ecosystem Diagnostics Analysis (EDA) was carried out in the Imiría Regional Conservation Area. Meetings were held with the local management committee and a field survey, covering most of Lake Imiría was carried out.

The first workshop was held in Pucallpa with the participation of the management team and the management committee of the Regional Conservation Area, representatives of the regional government of Ucayali and the district of Masisea, the Peruvian Ministry of Environment, SERNANP, indigenous organisations, the Alas Peruanas University, the NGO Naturaleza y Cultura Internacional, USAID, UNDP, staff from the CoGAP project, as well as a consultant of Ecoperu, the company in charge of the development of the management plan. During the two days of the workshop, the participants developed a detailed conceptual model, reflecting the complex situation of the conservation site. The results, including the model, were presented to participants in the form of a report, prior to the implementation of the second workshop.

During the second workshop, which was held in October 2013 in the city of Pucallpa, the participants evaluated the existing strategies implemented by the diverse stakeholders active within the region. Later on, they developed new complementary strategies, a process that was very productive since the activities of the management team were still very limited at that point. The results were returned to the participants in form of a report, including detailed recommendations.

The GIZ project supported the local conservation efforts of the government of the Puerto Inca Province with a systemic analysis of risk and vulnerability.

In October 2013, an EDA was carried out in Puerto Inca. The fast change and presence of several potential threats to ecosystems and local conservation efforts were documented and confirmed in workshop discussions. The local government, representatives of several regional government agencies, including the regional environmental committee, indigenous organisations, and representatives of the private sector participated in the workshop. The resulting conceptual model was very detailed, especially in terms of the political and legal aspects. This could be attributed to the participation of many representatives of local and regional governments. A report documenting the results of the workshop was prepared and distributed to the participants.

Results

Overall, the conceptual models of the three assessments were very similar. The minor differences were mainly variations in the depth of detail of the analysis, caused by the fact that each group highlighted the aspects that were of special local interest. Therefore, the three local models were integrated to form one large conceptual model, covering the whole region.

Generally, the ecosystems of the region were still in good condition, probably because of the remoteness of the conservation sites in the past. However, the improvement of the road network in recent years, as well as the growing international demand for natural resources has triggered interest from international corporations in the region. The effects of the new road have been dramatic and some of the related elements that were identified as future problems during the first assessment in 2011 had already materialised by 2013, thus underlining the fast changes that the region currently experiences. This became especially evident during the analysis of the Puerto Inca Province. Within a few years, extensive areas of forest had been cleared and were replaced by plantations, mainly palm oil and timber. The increased production volume is reflected in the growing number of palm oil processing plants, sawmills and the availability of agrochemicals. The local government gave the impression of being overwhelmed by the speed and extent of these changes and it seemed unlikely, that they would be able to stop these processes without the intervention of the national government. The ongoing degradation of ecosystems will lead to the loss of functionality and reduction of ecosystem services, which are highly important for the local population. This is particularly the case for ecosystem services related to the water cycle, given that most people are dependent on agriculture and/or cattle farming.

In comparison to the other two assessment areas, the state of the ecosystems of the Imiría Regional Conservation Area was exceptionally low. The natural resources of the lake system have been overexploited for many years due to its proximity to Pucallpa, the wealth of its natural resources and the lack of control. This has resulted in a loss of ecosystem functionality.

This is especially critical for the local population, since their livelihoods depend heavily on the ecosystems. The enforcement of laws and the control of the use of natural resources will therefore be major tasks for the local management team. Tasks, which the local management team was still unable to fulfil at the time of the assessment due to institutional weaknesses, included the lack of financing and personnel, limited management capacity and limited knowledge of laws and regulations.

Fortunately, there is the support of several NGOs and governmental institutions. Yet their activities still lacked coordination, which has led to a duplication of activities as well as rising conflict between some of the stakeholders. The need to diversify the activities of the different supporting stakeholders was consequently identified during the assessment.

All vulnerability assessments independently identified phenomena related to climate change that put stress on biodiversity and, directly or indirectly, caused suffering and damage in the communities that depend on these resources. The following issues relating to climate change were mentioned:

- More severe and frequent flooding,

- Intensification of the frequency and duration of droughts,

- Drying up of lagoons and clay licks,

- Reduction in the flow of rivers and streams,

- Very variable water level patterns,

- Very small fish populations in the dry season,

- Landslides in montane forest areas,

- Increase in trees uprooted by wind and

- Changes in flowering and fruiting seasons.

The causes of change affecting biodiversity associated with agriculture, logging, river pollution, etc. were also analysed. There was discussion of how local population growth and immigration from other parts of the country, facilitated by improved access to the region, have increased demographic pressure on the area and demands on agricultural production.

The main causes mentioned were lack of control, poor governance, the failure of the authorities to prioritise conservation, and problems relating to culture, local practices and capacities. There was also discussion of external factors affecting the reserve, including coca growing, boosted by growing international demand for cocaine, international demand for land and crops and rising international gold prices, all of which has led to the increase of illegal mining activities in the buffer zone and the El Sira Communal Reserve itself.

Climate change was identified by participants as a factor exacerbating the current situation by causing mountain dwellers to migrate thus leading to a decline in crop productivity and the take-over by agro-business with inevitable consequences of rapid expansion of the agricultural frontier. This was another good example of climate change generating not just direct impacts on ecosystems and humans, but also triggering indirect impacts, both locally and regionally.

The need for sustainable economic activities for the region in order to protect its biodiversity was pointed out by the participants of all three assessments.

Outcomes and conclusions

The El Sira MARISCO workshop served as a useful pilot exercise for the various practitioners involved in conservation management planning. Overall, the people and institutions involved were satisfied with the work and the results. The participants appreciated the method since it facilitated the active participation of local stakeholders and those with knowledge of the area, and also guided the discussion and analysis step by step through very complicated and complex issues. Furthermore, the process helped to raise the awareness amongst participants drawn from very different backgrounds and with a range of divergent skills and level of understanding about vulnerability, risk/threat dynamics and contributing factors.

The participants acknowledged and affirmed that the management goals for the area should be even more closely focused on maintaining and strengthening the functionality of the reserve and reducing vulnerability. Climate change and adaptation were recognised as cross-cutting issues that can no longer be analysed or addressed in a piecemeal manner.

Some of the existing strategies implemented in accordance with the reserve’s master plan and classed as top priority were identified as cross-cutting strategies. They included ‘developing/promoting participation/ gender equity’, ‘communication’, ‘environmental education’ and ‘developing community capacities’. The existing strategy for ‘raising awareness and mobilising public opinion about deforestation’ was a more specific strategy that was also prioritised.

In order to reduce the area’s vulnerability to climate change and other risks and factors, complementary strategies were designed to promote cultural activities and the recording of traditional knowledge for use in the future. It was felt that local knowledge was valued and needed to provide support to enable communities to adapt to climate change and prepare for extreme weather events (including assistance to improve agricultural production), as well as to promote fire control and prevention and to support local governments in their development planning, including the climate change perspective.

Given the complexity of the threats and the high inter-linkage between the contributing factors, some of the challenges had to be addressed at national level. The consultants informed the MINAM and SERNANP during a briefing about the results of the workshops and made the following recommendations: to support processes at institutional level to link protected and forest areas (networks, connectivity) in the region; , to formulate plans for land use in the proximity of roads; to especially encourage local consultation before the construction of works affecting protected nature areas; and to promote coherent and concerted planning with the authorities; and to promote the creation of an association with other community reserves in the Peruvian Amazon.

During a workshop held in February 2012 in Pucallpa, the team of the GIZ project tried to incorporate the results of the analysis in the Annual Action Plan of the El Sira Communal Reserve. Unfortunately, this was not possible since once established, the Annual Action Plan can hardly be modified, due to institutional rules within the SERNANP. The incorporation of the findings and complementary strategies was postponed to 2013, during which both Master Plan and Annual Action Plan were supposed to be renewed.

It is, therefore, recommended to take the validity of the Annual and Master Plans into account when planning the workshops and to ensure that a sufficiently long time period for assistance and support during the implementation of the results is guaranteed.

Nevertheless, the results of the analysis stimulated the development of new activities of the GIZ project. For example, the project developed an activity called “Biodiversity Fare e” (Ferias de biodiversidad) to contribute to the complementary strategy to promote cultural activities and the recording of traditional knowledge for future use, classified in the analysis as top priority. This will promote traditional knowledge among school children and to revaluate the use of local biodiversity. These fares were held very successfully with considerable interest shown by people from the villages and local communities as well as by participants from ECOSIRA and SERNANP.

In retrospect, the analysis of 2011 still included a huge blindspot; factors relating to institutional weaknesses were completely absent. This blindspot turned out to be quite important and can only be explained by the harmonious relationship between the park management and the administration partner at the moment of the analysis. Personnel changes within ECOSIRA and the park administration, and the lack of financial support from ECOSIRA, coupled with problems of administrating to such a large territory had major consequences on the functionality and quality of the management of the community reserve. The revision of the conceptual model provides an ideal opportunity to incorporate these factors and to address its implications on the effectiveness of the conservation strategies. Given the importance of the negative impacts of institutional weaknesses stressed during the workshops it is strongly recommended to address this particular issue during the analysis.

As mentioned above, the Imiría exercise was carried out during the phase to develop the management plan of the Regional Conservation Area. In order to guarantee the implementation of the results in the developing management plan, all relevant stakeholders involved in this process were invited to the workshops and all played an active role in the exercise. . The local management team, in particular, was very pleased with the outcomes, since they were the result of a participatory process. Unfortunately, only a very limited part of the results was adopted in the official management plan in the end. The main reasons for this failure seem to be disinterest of the consultant responsible for the elaboration of the management plan and the resistance of the regional government to introduce new ideas in the management design. Due to institutional weaknesses, the local management team was unable to insist on the incorporation of the results on their own and would have needed stronger support by the other stakeholders in order to achieve their goal.

This outcome underlines the importance of ongoing support and guidance of local management teams during the implementation of results. Therefore, it is recommended to include at least an additional year for the implementation during the planning of a MARISCO exercise.

ConMod_Amazon_V2_AXS-2014-10-27 (1).pdf

PDF-Dokument [451.7 KB]

Testimony of Mr Rudy Valdivia, head of strategic planning, SERNANP (National Service of Natural Protected Areas)

‘We value the results of the exercise, particularly in view of the fact that they contribute to developing the capacities of the actors involved in the management of our protected nature areas, so that they can address the challenges they face and future risks in a more strategic way. In this context, it is important for management strategies to incorporate the principles of precaution and prevention, so that we can be more proactive rather than simply responding to acute crises.

Risk management in biodiversity conservation contributes to the wellbeing of the people who rely on ecosystem services.’

Testimony of Mr Luis Saavedra, head of the El Sira Community Reserve

‘Those of us who are involved in the intense work associated with the management of the El Sira Community Reserve are aware of the complexity of the situation it faces. This analysis exercise, carried out using the MARISCO method, has facilitated a participatory process to familiarise a diverse and heterogeneous group of actors with the risks and factors that contribute to threats affecting biodiversity. I must admit that our demanding day-to-day work to meet urgent needs leaves us with very little time to reflect on the dynamics of the situation and broader, more comprehensive strategies.

However, the results of the systematic analysis confirm that while the reserve is still relatively well conserved, the combination of threats and risks identified is certainly a cause for concern. We realise that we need to think and act big and involve all those concerned with its conservation’.

References

Aichinger M (1991) A new species of poison-dart frog (Anura, Dendrobatidae) from the Serrania de Sira, Peru. Herpetologica, 47: 1-8.

Benavides M (2005) Atlas de Comunidades Nativas de la Selva Central. Lima, Peru: Instituto del Bien Comun.

Castro G, Alfaro L and Werbrouck P (2001) A partnership between government and indigenous people for managing protected areas in Peru. Parks 11 (2): 6-13.

Duellman W and Toft C (1979) Anurans from Serrania de Sira. Amazonian Peru: Taxonomy and biogeography. Herpetologica, 35 (1): 60-70.

ENVIROLAB PERÚ SAC (2010) Informe técnico final “Evaluación de Recursos hídricos en las Regiones de Pasco, Ayacucho, Cusco, Puno y Ucayali. Ministerio de la Producción. Envirolab Perú SAC. Pucallpa, Peru. 105 pp.

Finer M, Jenkins C, Pimm S, Keane B and Ross C (2008) Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, iodiversit, and indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932.

Finer M and Orta-Martinez M (2010) A second hydrocarbon boom threatens the Peruvain Amazon: trends, projections, and policy implications. Environmental Research Letters 5: 014012

Gobierno Regional de Ucayali (2004) Diagnóstico de Recursos Naturales de la Región de Ucayali, Pucallpa-Perú.. Gerencia de Recursos Naturales y Gestión de Medio Ambiente. Pucallpa, Peru. 278 pp.

González O (1998) Birds of the lowland forest of Cerros del Sira, central Peru. Cotinga, 9: 57-60.

Graves G and Weske J (1987) Tangara phillipsi, a new species of tanager from Cerros del Sira, eastern Peru. Wilson Bull. 99: 1-6.

Ibisch P.L. and Nowicki C. (2011) Análisis de la vulnerabilidad y estrategias para la adaptación al cambio climático en la Reserva Comunal El Sira –Perú. Experiencias con la metodología en el Proyecto “El Sira - GIZ”, Perú. Aplicación del método: Manejo Adaptativo de RIesgo y vulnerabilidad en Sitios de Conservación (MARISCO) en la Amazonia peruana. Ed.: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Proyecto Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático en la Reserva Comunal “El Sira”, Lima, Peru (Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Nº: 2011-14981).

Ibisch P.L. and Nowicki C. (2012) Vulnerability analysis and strategies for climate change adaptation in the El Sira Community Reserve, Peru. Experiences using the methodology in the El Sira-GIZ project, Peru. Application of the method: Adaptive Risk and vulnerability Management at Conservation Sites (MARISCO) in the Peruvian Amazon. Ed.: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Proyecto Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático en la Reserva Comunal “El Sira”, Lima, Peru.

Inrena. Intendency of Protected Natural Areas, National Institute of Natural Resources; El Sira Communal Reserve Technical Report, May 2001.

Lotters S and Hensl M (2000) A new species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) from the Serranía de Sira, Amazonian Peru. Jr. Herpetology, 34 (2): 169-173.

Marmontel, M. (2008) Trichechus inunguis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 07 August 2014Scott G (1979) Grassland Development in the Gran Pajonal of Eastern Peru. A study of soil-vegetation nutrient systems. Hawaii Monographs in Geography.

Mee A, Ohlson J, Stewart I, Wilson M, Örn P and Diaz J (2002) The Cerros del Sira revisited: birds of submontane and montane forest. Cotinga, 18: 46-57.

Ministry of Transport and Communication, OGPP, Oficina de Estadistica (2012) http://www.mtc.gob.pe/estadisticas/files/mapas/transportes/infraestructura/01_vial/proyectos_inversion_2012.pdf

Monteagudo A and Huaman M (2010) Catalog of woody plants of the Selva Central of Peru. Arnaldoa, 17 (2): 203-242.

Weske J and Terborgh JW (1971) A new subspecies of curassow of the genus Pauxi from Peru. Auk, 88: 233-238.

Bachelor thesis applying an early MARISCO approach for a situation analysis of the Alto Purus National Park, Peru

Teresa L. Reubel, Robert S. R. Williams, Danilo Jordan, Juvenal Silva & Eddy Torres

General setting

An early version of the MARISCO approach was applied in a Bachelor thesis in International Forest Ecosystem Management at Eberswalde University for Sustainable

Development to reorganise and refine the results from four workshops held in Puerto Maldonado, Peru during an internship with the Frankfurt Zoological Society’s Andes to Amazon Conservation Programme

in February and March 2011. The results of the study aimed at providing orientation and facilitate the park management for the formulation of the National Park’s new management

plan. The Alto Purus National Park is by far the largest protected area in Peru, containing a high level of biodiversity. It is, however, exposed to a number

of developing socio-economic pressures.

Box 1: Alto Purus National Park

The Alto Purus National Park is located in the Amazon rainforest area in south-eastern Peru. The Park is the 11th of 13 National Parks in the country and was created on November 20, 2004 by means of the Supreme Decree Nº040-2004-AG. The park is situated in the province of Purus in the department of Ucayali and the province of Tahuamanu in the department of Madre de Dios. To the north and east the park borders Brazil. The bordering areas in Brazil are areas classified as indigenous lands or state parks. Three buffer zones are designated; one in the northeast bordering the town of Puerto Esperanza, the other in the south-eastern part, and the third covering the western border of the National Park. The buffer zones cover areas of Territorial Reserves (established and managed by the Ministry of Culture to protected indigenous groups in voluntary isolation) and forest concessions: in the northeast, the park limits the Purus Communal Reserve, in the south-eastern corner of the park the Madre de Dios Territioral Reserve (further on bordering forest concessions), and in the north-western corner the Muruanahua Territorial Reserve. To the west, it borders forest concessions. Lastly, the Park is connected to Manu National Park in the South. Inside the National Park a Territorial Reserve has been assigned to the Mashco-Piro indigenous people. Encompassing 2,510,694.41 hectares, Alto Purus National Park is the largest protected area in the country.

The park has humid equatorial rainforest climate. From October to May, the rainy season brings more than 80 per cent of the annual precipitation. The annual average precipitation is 1800 mm. By tendency, the rainfall increases from the southeast to the northeast (INRENA, 2005, p. 29). The rains cause the water level in rivers to rise and flood the river banks and low-lying adjacent forest. There is a short dry season from June to August.

The area is characterised by two major landscapes: hills and floodplains. The former are mainly located in the western and south-western part of the National Park, whereas the alluvial floodplains cover the remaining parts of the Park.

The Purus River, after which the National Park was named, together with its tributary rivers Cujar and Curiuja, represents the main river basin of the area. Further, the headwaters of Chandless, Yaco, Tahuamanu, Las Piedras, San Francisco and Lidia rivers form the waterways of the southern and eastern area.

In accordance to INRENA (2005, pp. 32-35), the following forest types have been distinguished within the Park: wet lowland forest, hydrophytic palm forest, wet terrace forest, and wet hillside forest. The forest cover is heterogeneous and well developed, with a canopy reaching up to 35m.

The park’s ecosystems offer important ecosystem services: The hydrographical network within the park produces water resources that are of importance on national and international level. The park constitutes part of the Vilcabamba Ambóro Biological Corridor stretching from Peru to Bolivia (AVISA SZF PERU, 2011), enabling genetic exchange. It produces fresh air, acts as CO2 storage, regulates the local climate and provides habitat for many species and indigenous groups.

It is home to a variety of endangered and endemic flora and fauna, such as the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), the yellow-spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis), the arrau river turtle (Podocnemis expansa), the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), which IUCN Red List categorised as “near Threatened” (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2011), as well as Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and Tropical Cedar (Cedrela odorata). The area’s wildlife is extremely diverse, abundant and well-preserved. The few studies conducted indicate that the region is located in one of the most diverse areas for bird and mammal species (Shoobridge, 2003, p. 22).

The area is inhabited by groups of indigenous people, including several that have avoided contact with the outside world and live in voluntary isolation. According to Michael and Beier (2003, p.149), the two main known ethnic groups are the Mashco and the Curanjeños. It is assumed, according to Shoobridge (2003, p.170), that there are three main groups living in a nomadic fashion. The first group of people is moving along the headwaters of the rivers Yaco and Chandless as well as the Santa Cruz creek. The second group moves along the headwaters of the rivers Cujar, Curuja and Las Piedras and perhaps the Manu river to the south. A third group moves along the headwaters of Curanja towards Brazil (Shoobridge, 2003, p. 170).

The former Management Plan for the years 2005 through 2010 formulates that the park aims to conserve a representative sample of wet tropical forest and its transitional Life Zones, the area’s ecosystem services and valuable and endangered flora and fauna. Moreover, the park aims to protect the indigenous in voluntary isolation and/or in initial or sporadic contact and guarantee their physical and cultural integrity. Furthermore, the National Park aims to promote the investigation of biodiversity, education, and tourism in determined areas. (INRENA, 2005, p. 21) However, to date there has been no tourism in the area.

Since 2010, the Park is managed by SERNANP. SERNANP is the institution responsible for protected areas in Peru and under the roof of the ministry of environment. Formerly, this area was managed by INRENA (Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales). Previous to the establishment of the National Park, the area was protected as Alto Purus Reserved Zone since 2000.

In order to facilitate the protection of the park, Management Plans are formulated every five years. The first and latest Management Plan of the Alto Purus National Park was for the time from 2005 to 2010.

The park management is amongst others supported by WWF as well as FZS, who support the work of the park guards throughthjrough training, equipment, logistics and infrastructure.

Work flow

The group was composed of members from NGOs working in the rainforest area of Madre de Dios and not for the National Park, except for one person that formerly worked there.

The goal of the cooperation with different NGOs and a national reserve was on the one hand to involve different stakeholders (with same goals) and to profit from their (local) knowledge, and on the other hand to introduce the use of the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation (OS) and the corresponding software Miradi to develop capacity. By using the OS, basic data like targets, direct threats and indirect threats for the conceptual model was collected and processed in Miradi.

After fieldwork, the conceptual model was broadened through literature and internet research, as well as knowledge exchange with Rob Williams, director of FZS’s Peru, and Eddy Torres, specialist of Alto Purus NP, as well as Danilo Jordan and Juvenal Silva from FZS Peru Then, all gathered information was analysed applying an early version of the MARISCO approach. The extended and revised factors and direct threats of the model were arranged in thematic groups under management, bio-physical, socio-economic, political, lack of knowledge, lack of conditions, climate change and development. All factors and direct threats were assessed using a set of criteria: Criticality, current and future dynamics, systemic activity, manageability and knowledge. The sum of the first three mentioned criteria amounted to the strategic relevance. Accordingly, they were ranked hierarchically.

In order to integrate the team, the park management of APNP and other knowledgeable people in the ongoing process, the analysis was shared with them for verification and/or alterations of the model and ranking. Only one reply was received. Incorporating this reply into the analysis, the thesis is based on the overall results of the described process.

Results

MARISCO proved as a very useful tool to structure a high amount of information and therefore made it possible to generate an overview of a complex situation and its interconnections. Especially valuable was the look into the future development of the threats and the consideration of risks for the park.

Conservation objects

In order to represent the area’s full array of biodiversity, two ecosystem types were selected; forest and aquatic ecosystems. They subsume flora and fauna that share the same threats.

Further, the conservation target high-value tree species was identified, lumping especially Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) and Tropical Cedar (Cedrela odorata). The two species are listed as vulnerable in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) represents another conservation target. The animal is very sensitive to human presence; they are disturbed very easily, which results in their retreat. Giant otters are bioindicators for health of tropical lowlands in southeastern Peru. They are top predators that play an important role in ecosystem dynamics. Moreover, the animal is listed as endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species with a decreasing population trend. Altogether, the giant otter was selected as charismatic flagship species for the region.

As human welfare object, isolation and health of indigenous people was identified. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) supports their rights of self-determination, autonomy, liberty, integrity, and health. The Peruvian State protects these indigenous peoples and their territories under law 28736. They are vulnerable to diseases such as influenza and their survival depends on them being able to move freely to access resources they need without contact from the outside world. In accordance with the National Park’s objectives, the protection of indigenous people in voluntary isolation has been targeted.

Direct threats

Logging activities have almost been eliminated since the establishment of the park in 2004. The present amount of logging is not a great threat to Mahogany and Tropical Cedar, in monetary terms the most valuable tree species of that area. However, the preceding logging of the trees has strongly decreased the species’ distribution in the region, making them vulnerable. Effective conservation measures in form of control posts have decreased logging activities tremendously and also the illegal hunting carried out by loggers. Unsustainable fishing outside the park is influencing migratory fish species, especially in the river Tahuamanu in Madre de Dios. Yet, the National Park seems large enough to sustain healthy fish populations. Livestock farming permits the transmission of diseases to wildlife; nonetheless, the habitat for wildlife populations should be large enough to cope with that. Land use changes in form of settlements and associated roads as well as agriculture have been made. Though, the increasing pressure on the park has been resisted so far and except of one settlement at the western border and another one inside on the river Yaco, nearly no influence can be seen on the park.

The impacts resulting from the described direct threats are so small, that the vulnerability of the targets and the park is quite low. The remoteness of the protected area and its large size favours the current conservation situation. Except for the decrease of high-value trees and wildlife, the biodiversity of the Alto Purus National Park seems to have only marginally decreased.

This suggests that the park faces no major challenges other than that of having to intensify existing conservation measures. Nevertheless, the current situation is not stable and fixed in time. Taking a look at the evaluation of the direct threats and contributing factors, the future development indicates risks that provoke changes in the current protection status of the National Park.

Looking at the complexity of the conceptual model, it illustrates the interwoven, complex socio-economic and political situation of the influencing area of the park: given time, population growth through migration and local population growth, as well as the enduring poverty and lack of alternative income possibilities, suggest that the pressure on the park will rise tremendously. Once these developments arise and the pressure increases, the currently difficult park management factors will become a crucial problem for a continued conservation. Furthermore, the estimated lack of internal knowledge can accelerate the negative effects of these developments.

The evaluation of the socio-economic factors showed that logging has a high dependency on the international demand and therefore timber prices. At the moment, logging inside the protected area is neither widespread, nor profitable due to low timber prices and the disappearance of the species in the proximity of the rivers. With rising prices, logging becomes more lucrative and attractive again. Taking from the conceptual model, the entangled relationship between poverty, income necessity, and the expansion of settlements in the area increases the demographic pressure and with it, it accelerates the pressure on the resource of high-value trees. Moreover, the existing problem of the ambiguous legality of the Tahuamanu control post can easily be uncovered and could result in the failure of its protective function[1]. Thus, logging activities, even though almost extinguished for now, could pose a much greater risk for the area in the near future.

Similarly, fishing could affect the National Park. Presently fishing activities are only affecting migratory fish species. If fishermen find out that the control posts cannot prevent their entrance, there is a very high probability that they will enter the buffer zone and further on the park driven by overfished areas downstream and the need for income. Due to the latter problem, it can be assumed that fishermen will try to enter the park regardless of their knowledge concerning the ambiguous legality of the control posts.

Likewise, the strong increasing future trend of population growth as well as that of the expansion of settlements and the agricultural frontier accelerate the pressure of land use changes on the protected area.

Apart from the described risks, the possibility of a road being constructed to establish a connection to the Interoceanica highway from Puerto Esperanza, which would pass through the park and the territorial reserve needs to be incorporated into the scenario: the construction of a road through the park would intensify all described current threats. Considering the diverse strong interest groups of religious organisations, loggers and possibly the government, in favour of the road, this presents a great risk to the protected area.

Such a terrestrial connection through the park would allow people to enter the area and settle, as can be observed along parts of the Interoceanica in Brazil and Peru. This results in deforestation for housing and agriculture, and opens the area for extractive activities such as logging. Religious groups still intend to establish contact with isolated indigenous groups and such a road would facilitate access. Lower prices for Mahogany won’t play an important role anymore, because new areas that weren’t accessible before can now be exploited. The road would also allow illegal drug traffickers to open new access routes from Peru into Brazil.

The risk of the road construction through the National Park may also accelerate the risk of gold mining inside the park; the rivers the planned road would cross are no yet known to be gold-bearing but miners are always seeking new areas. Especially, because gold mining was seen as not profitable until now, due to missing access possibilities and lower gold content in the sediments. With a rising population pressure and missing income sources, mining for gold in an area that has been opened up is a possible consequence. Gold mining leaves behind cratered moonscapes; the foregone ecosystems are fully destroyed. Hence, the construction of this road would be hazardous to the park and its conservation and human inhabitants as well as those in neighbouring areas in Brazil (especially for indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation that use the region as transit area from Peru to Brazil).

Climate change is likely to significantly affect the ecosystems and could lead to irreversible damage, especially if the park is already susceptible to damage due to described developments. Rising temperatures and altering precipitations by the 2050s are predicted for the area. Annually altering precipitations as well as decreases in precipitation during the dry season could exaggerate the impacts of higher temperatures. These changes could significantly affect the forest and aquatic ecosystems and with it the giant otter; the vulnerability of all targets are likely to increase.

Vulnerabilities

Mahogany and Tropical Cedar could significantly be affected by the described risks. Their naturally low distribution and the selective extraction activities make them highly vulnerable.

The forest and aquatic ecosystems are heavily impacted by land use changes, logging, gold mining, and fragmentation and are thus also highly vulnerable.

Being sensitive to disturbance, the distribution of the giant otter will most probably strongly decrease, making it extremely vulnerable.

The lives and natural environment of indigenous groups could be seriously endangered, if access is granted through the road project. And even without this road, their lives are endangered: Religious groups heavily threaten the indigenous peoples’ integrity. Additionally, the invasion of the region with wood, gold and fish extractors would restrict their isolation and could as well harm their health or even lives. Their susceptibility to diseases makes them highly vulnerable.

Opportunities

Opportunities present a possibility to influence the covered risks and the arising impacts. The evaluation of the opportunities suggests that some are more promising than others, although none of them will be able to stand alone against the threats connected with them. Rather, the combined use of them can support the mitigation of the threats and risks.

The impacts of climate change need to be taken into account. How this can be facilitated, worldwide researchers are finding out and publishing. Experts in this field can give recommendations on how to adapt the management in proactively dealing with the impacts.

Several Opportunities can support the mitigation of the risks that especially arise out of the demographic pressure and lack of income generating activities. While up-to-date conservation measures of the park concentrate on preventing people from entering the park by control posts, it is desirable to enlarge the measures onto a much wider scale. Mostly, people are not tempted to extract resources from the park to squeeze profit but because they depend on them. Giving people a perspective in that they won’t depend on entering the protected area anymore seems necessary. Income generation through sustainable practices and programs such as aquaculture, agroforestry systems, Brazil nut and forest concessions and FSC certification hold promise in diminishing the pressure on the ecosystems locally and on the park. Additionally, agreements such as a bi-national fishing management plan could, if enforced, promote sustainable fishing practices.

To meet the mitigation of the risk of a change in conservation law, the REDD+ program could support and lessen the risk of de-gazettement, by adding value to the park. Dudley (2010) also evaluated that forests in protected areas offer a great potential for REDD+ projects and incentives against de-gazettement. Finally, it could take its part in the prevention of the connection of Puerto Esperanza to the Interoceanica.

Outcomes and conclusions

During the workshop phase in Peru, the application of the Open Standards helped to structure first inputs. As the information input began to grow working solely on the topic, the first author felt that the MARISCO method proved to be advantageous for structuring the newly gained knowledge and making it more appealing to the eye and therefore comprehensible. The methodological process helped her to organise her thoughts. With the gained overview of the situation and information, she could see where more input was needed and could therefore complete the analysis.

She especially appreciated the look it gave into the future development of the threats and the consideration of risks for the park: The simple evaluation of the threats showed a well preserved National Park that suggested no significant problems. A structured look into the future revealed important risks and negative developments that would influence the park more strongly than expected. The steps to the risk analysis helped her to make the assessment comparable and with that produce significant results.

However, working on this alone, and not in a team, was overwhelming sometimes: With the methodology not finalised, so definitions not yet set, clear guidance was missing. Additionally, some of the rating of, for example, knowledge proved to be difficult without the management team present.

Nonetheless, the approach added perspectives to the analysis that gave new important insights into the complexity of the situation. It can be concluded that using MARISCO for the purpose of a thesis, is very useful to structure the work and to gain new comprehensions into a topic.

References

AVISA SZF PERU, 2011. Pronunciamiento a la opinion pública, sobre la pretendida carretera que atentaria el Parque Nacional "Alto Purus". [online] Available at: www.szfperu.org/noticias07.html [Accessed 23 July 2014].

Dudley, N., 2010. Protected Areas as Tools for REDD: An Issues Paper for WWF. [pdf] Available at: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/about/pifs/symposia/fcfs/2010-fcfs-briefing-materials/dudley-final.pdf [Accessed 23 July 2014].

INRENA, 2005. Parque Nacional Alto Purus Plan Maestro 2005-2010. Lima.

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2011. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). [online] Available at: www.iucnredlist.org [Accessed 23 July 2014].

Michael, L. & Beier, C., 2003. Indígenas en Aislamiento Voluntario en la Región del Alto Purus. In Alto Purus Biodiversidad, Conservación y Manejo. Lima: Duke University. pp.149-62.

Shoobridge, D., 2003. Amenazas a la Conservación Socioambiental del Alto Purus. In R. Leite Pitmann, N. Pitmann & P. Álvarez, eds. Alto Purus Biodiversidad, Conservación y Manejo. Lima: Duke University. pp.165-75.

UN General Assembly, 2007. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations General Assembly.

[1] At the time of publication this problem this issue is considered resolved.